The Martinengo Bastion and Makasi Gate are prominent features of the impressive Venetian walls that encircle Heraklion, Crete. Built in the 16th century, these fortifications played a crucial role in the city’s defense against the Ottoman Empire.

The Fortifications of Heraklion

Early Walls

The earliest walls of Heraklion date back to the Byzantine era. In 824, Arab forces captured the city and erected walls of unbaked bricks, surrounding the city with a trench. The city, then known as Rabdh al-Khandaq (Trench Castle), became the capital of the Emirate of Crete.

In 961, the Byzantines, led by Nikephoros II Phokas, recaptured Heraklion. They demolished the Arab fortifications and built a new fort named “Rokka.” As the settlement grew, the Byzantines constructed new walls on the site of the previous Arab walls. Remains of these Byzantine walls can still be found near Heraklion’s harbor.

Venetian Walls

In the early 13th century, the Republic of Venice gained control of Crete. Initially, they utilized the existing Byzantine walls, making modifications as needed. However, the fall of Constantinople in 1453 and the rise of the Ottoman Empire prompted the Venetians to build a new, more formidable fortification system.

Construction of the new walls began in 1462. The walls were designed by prominent military architects Michele Sanmicheli and Giulio Savorgnan. They were built over a century, and various outworks were added over the years to further strengthen the fortifications.

Ottoman Rule and Modernization

The fifth Ottoman-Venetian War (1645-1669) saw the Ottoman navy arrive off Crete on June 23, 1645. While Canea and the Fortezza of Rethymno fell to the Ottomans, the Venetian garrison in Candia (Heraklion) managed to resist for 21 years, making the Siege of Candia the second-longest siege in history. The city surrendered in 1669, and the Venetians were allowed to leave peacefully, sparing the city from being sacked.

After the Ottoman conquest, the fortifications were repaired and maintained. The bastions were given Turkish names; for example, Martinengo Bastion became Giouksek Tabia. The Ottomans also built a small fort known as Little Koules near the Rocca al Mare (now known as the Koules Fortress). This was later demolished in 1936 during the city’s modernization.

The walls sustained damage from German aerial bombardment during World War II, but the damage was repaired. After the war, some outworks were demolished to make way for modern buildings. There were even suggestions to demolish the entire city walls, but this never happened. Today, the walls remain largely intact, standing as some of the best-preserved Venetian fortifications in Europe.

Martinengo Bastion

The Martinengo Bastion is the largest and most southerly of the seven bastions on the landward side of the Heraklion Walls. It was named in honor of Gabriele Tadini di Martinengo, a distinguished Venetian military engineer who oversaw the fortification works in Crete in 1519. The bastion was designed to withstand cannon fire and provide a commanding view of the surrounding area.

The Tomb of Nikos Kazantzakis

The Martinengo Bastion is also the site of the tomb of the famous Cretan author Nikos Kazantzakis (1883-1957). Kazantzakis, known for his novels “Zorba the Greek” and “The Last Temptation of Christ,” is one of the most celebrated figures in modern Greek literature. His tomb, marked by a simple cross and a plaque with his name, is a place of pilgrimage for many admirers of his work.

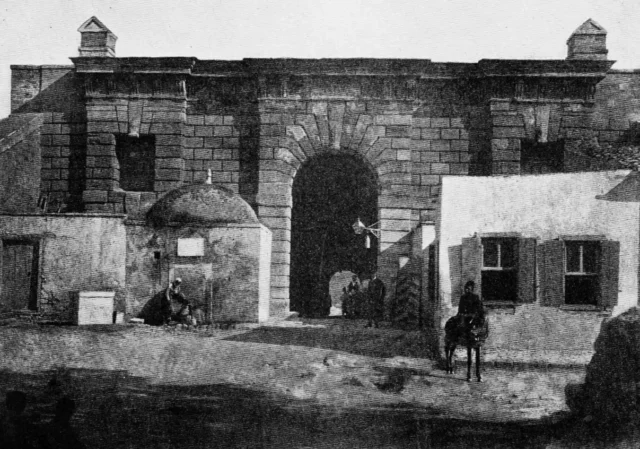

Makasi Gate

The Makasi Gate, also known as the Martinengo Gate, is a military gate located beneath the Martinengo Bastion. The name “Makasi” comes from the Turkish word for “locksmith.” Despite its military function, the gate features a monumental facade on the city side, built with careful attention to detail, as if it were a main gate.

A Place of Suffering and Remembrance

In more recent times, the Makasi Gate has been associated with one of the darkest periods in local and world history. During World War II, the occupying German forces used the gate as a detention center for prisoners of war and hostages before they were transported to concentration camps. This tragic event has transformed the gate into a place of remembrance.

In the first section of the gate, on the city side, memorial plaques list the names of the prisoners held there. The second section, leading to the eastern “low square” of the Martinengo Bastion, is planned to house an exhibition dedicated to the National Resistance. Today, the Makasi Gate serves as a Museum of Memory, commemorating the city’s history and the sacrifices of its people.

The Great Blockade of Crete

On June 15, 1943, the German forces, with the help of Cretan collaborators, implemented the “Great Blockade of Crete.” They arrested around 300 civilians without any incriminating evidence and imprisoned them in the Makasi Gate. Two weeks later, the prisoners were transported to Thessaloniki via Piraeus. From there, they were taken by train to the Zemun prisoner of war camp near Belgrade. On November 4, 1943, about half of the hostages were deported to the Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria, where they were forced to work as slave laborers for the German war industry. Most of them perished in the inhumane conditions.

Each year on June 15, a memorial ceremony is held at the Martinengo Bastion to commemorate the victims of the Great Blockade. Wreaths are laid at the three marble plaques inscribed with the names of the victims, which were placed there in May 1976. The Makasi Gate now serves as a venue for cultural events and exhibitions, keeping the memory of these tragic events alive.

The Deportation of Cretan Jews

The Martinengo Bastion is also linked to the tragic fate of the Cretan Jews. In 1941, there were 341 Jews living on the island, most of them in Chania and 26 in Heraklion. As part of the “Final Solution,” the Germans planned to deport them to the Auschwitz death camp. From May 8 to June 8, 1944, they were held prisoner in the Makasi Gate. The German occupiers then crammed the Jews, along with 48 other Cretan hostages and 122 Italian prisoners of war, onto the steamship “Tanais” to transport them to Piraeus. The ship was torpedoed 33 nautical miles northwest of Heraklion by an Allied submarine, and all the prisoners drowned.

Fortifications: Key Points

- Construction Period: 16th century

- Location: Southern side of the Heraklion Walls

- Historical Significance: Major defensive point, site of Nikos Kazantzakis’ tomb, place of remembrance for victims of World War II atrocities

- Current Status: Well-preserved, open to the public, serves as a Museum of Memory and a venue for cultural events

References

- Dretakis, Emmanouíl K. (2015). From Martinengo to Mauthausen. A one-way trip: Konstantinos Emm. Dretakis 1902-1945. Athens. Sources and related content

- Gerola, G. (1905). Monumenti Veneti nell’isola di Creta. Venice: Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti.

- Sythiakaki, V., Kanaki, E., & Bilmezi, C. (2015). Older Fortifications of Heraklion: A Different Approach Based on Recent Excavation Data. In Archaeological Work in Crete 3 (pp. 395-410). Rethymno: University of Crete.

- Gigourtakis, N. M. (Ed.). (2004). Heraklion and its Area: A Journey Through Time. Heraklion: Center for Cretan Literature.

There are no comments yet.